I've been asked by the irrepressible Ausculture Jess to post on a matter dear to my heart, about which she has been subjected to countless rants (well, one, and it wasn't very rant-like, and only lasted about a minute) and of which she would like to read more in a textual online form, since this will make it authoritative and quotable and perhaps true. Be warned, however: Jess does live in a barn and is periodically attacked by cats of various sizes who may or may not be under my mental control. She's moving out of the barn soon, though.

So: today's lesson is a quick primer in the subject of Historical Disco. Not disco which has been imbued with an historical patina now that we're several decades on from that colourful era of the late 70s and early 80s; no-no, sweet silly children, how innocent you all are! Take your places, now, and ready your notebooks. Afterwards, if you are good, there will be singing.

Disco was much reviled during its heyday, and its often bland excesses and vacuous hedonism leading, among other things, to the rise of seemingly-antithetical musical genres such as punk, mainstream metal and 80s white bloke rock. A rise of music which offered an antidote to disco wasn't just a taste thing, however, since it played upon a rich vein of social tensions only hinted at in the overt rhetoric. For many, disco was a feminine realm (and by implication, feminising, since it's always been ok for chicks to boogie, but John Travolta's uplit white-suited gyrations just ain't on, man). The hairy rock of Bruce Springsteen or the frenetic pogo-ing of Pistols fans didn't upset the boundaries: no chance of a guy being misconstrued, is all I'm saying.

Same with instrumentation: there's long been a divide between 'real' music (written and played by the band itself) and 'plastic' music, performed by artificial figureheads whose strings are pulled by some savvy Svengali in the studio. The issue of keepin' it real, of course, took on extra dimensions right about the time disco died, with the 'realness' of rock's talented white singer-songwriters suddenly challenged by the sample-heavy sequencer-ridden 'reality' of West Coast gangsta hip-hop.

"Disco will never be over. It will always live in our hearts and minds. Oh, for a few years, maybe for many years, it will be considered passe and ridiculous. It will be misrepresented and caricatured and sneered at. People will laugh about John Travolta, white polyester suits and platform shoes . . . Those who didn't understand will never understand. Disco was much more and much better than all that."

Impassioned and entirely unironic words from the classic disco film, The Last Days of Disco (released around the same time that the atrocious Studio 54 was stinking up silver screens everywhere). But why care? Why give two bits about a dance music genre which merely gave upwardly mobile white narcissists a chance to pretend they could dance?

Historical Disco might not answer that question, but it's pretty awesome anyway.

Every genre of music has something like it, I'm sure; if not quite its mirror, at least its penumbra, that grey area which unites the mode with its opposite. Literary Rock/Pop, for instance, Kate Bush's "Wuthering Heights" or the Velvet's "Venus in Furs" spring to mind. Or that style of funk/soul dedicated to marriage and making it work, long-term.

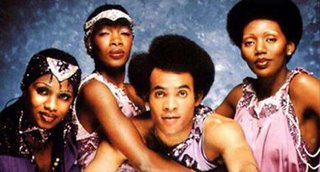

Historical Disco attempts to combine funky cheese-laden melodies with educational content, for no reason scientists have been able to discern so far. The undisputed heroes of the genre are Boney M, mainly due to three things: a) they were the creation of disco pioneer Frank Farian, who was German (Historical Disco invariably comes from Germany, b) they released not just one, but a swag of historical songs, and c) they were kind of the only group to actually record anything resembling historical disco.

Now, I know, I know, this last claim is a bit dubious. After all, Dschinghis Khan's "Moskau" often competes with Boney M's "Rasputin" as the most prominent HD title. But as most people realise, while Dschinghis Khan were kind of historical (if you count faux fur hats and bad Russian dancing as somehow historical) the song itself is just, you know, about Moscow. Not Moscow way back when, or anything. Ok, sure, you do get the line "City of mystery/So full of history". I guess I'll pay that. And they did possess what might well be the best stylist in the history of any form of music, anywhere, ever. I draw your attention to Exhibit A.

But "Rasputin" is a beast of a different character.

Consider the finely wrought lines of just a sample stanza, and see how they take dry textbook material and fashion it into a thing of great beauty:

"This man's just got to go!" declared his enemies

But the ladies begged "Don't you try to do it, please"

No doubt this Rasputin had lots of hidden charms

Though he was a brute they just fell into his arms

Then one night some men of higher standing

Set a trap, they're not to blame

"Come to visit us" they kept demanding

And he really came

Now, Boney M. were obviously as familiar with history as they were with things like syntax, cadence and meter, but they could sure slap some multi-layered vocals over a jumping bassline.

Farian put the band together after he'd scored a solo hit under the Boney M name; not exactly being of model looks, he decided to bring in four dancers, two of whom sang along on with him, and two of whom were just there for visual interest. Interestingly, he gave this tactic another outing when he formed Milli Vanilli years later (also composed of German session musos and fronted by miming dancers).

Why he decided to turn to history we'll never know. But along with "Rasputin," Boney M pumped out "Ma Baker," "Painter Man" (about Andy Warhol), "He Was a Steppenwolf" and a few others (including religious songs about little baby Jesus and stuff). Many featured instrumentation and arranged that could be described as inspired, but 'inspired' is a short trip from 'I'm totally confused as to why my dance music is telling me things about early twentieth century Russia."

And of course there's that lovely spoken word bit in the middle, in which a strange man attempting to sound like an authority but really just coming across as pissed seriously steps up to tell us that "When his drinking and his lusting and his hunger for power became known to more and more people, the demands to do something about this outrageous man became louder and louder!"

Further listening: Falco's "Rock Me Amadeus" (also in German, of course, though Austrian in origin, and more New Wave than disco); ABBA's "Waterloo" and "Fernando"; Dschingis Khan's "Dschinghis Khan" (less popular than "Moskau" but actually about an historical figure which helps) as well as other songs such as "Samurai"...uh, I can't think of any more and I'm a bit bored.

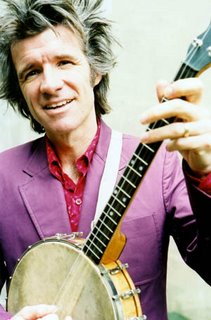

Dan Zanes plugs history to pre-teens. He's on at the Melbourne Festival this year; I saw him on Sunday and it was a pleasant experience. He didn't play any of my favourite tunes, which are the bolshie depression era work-songs or the gospelly blues laments or the sea shanty-style drinkin' songs; I mainly like these because I think it's an excellent idea for a four year-old to ask his or her mother what's the origin of lyrics like:

Take the two old parties, mister

No difference in them I can see

But with a farmer–labor party

We could set the people free

Seriously?

What about the simplicity of:

Pay me, you owe me

Pay me my money down

Pay me or go to jail

Pay me my money down!

Or the 13 year old kid singing:

Well it's all for me grog, me noggin’ noggin’ grog,

all for me beer and tobacco.

For I spent all me tin with the ladies drinking gin,

Far across the western ocean I must wander.

Yes.

I interviewed Dan a little while ago and he said some stuff I liked. It's more than I expected. I'll just quote him verbatim.

When my daughter was born I had this idea in my head of what I thought everybody was listening to. I didn't know anything about parents or parenting. I didn't know anything! I grew up listening to a lot of folk music, Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seger and all that stuff, and I just assumed that that's the kind of music that people were playing for their kids, just updated versions of all that. And I went into the record store to get some and it seemed like everything was tied into a TV show or a movie, it just felt very corporate. Not that there's anything wrong with that, but that was all I found.

And then I looked a little harder, and then there's always been great stuff for kids and families. So I eventually found lots of stuff, just not in the mainstream. But I didn't find that handmade sound that I was hearing in my head. For me, I was just trying to update Folkways Records. That was all I was really thinking about. Try and write a couple of good ones along the way, and make the kind of music that I used to hear, that made me want to play myself.

That's the name of the game, if you hear something and...you know, we played down at the Andy Warhol museum last week down in Pittsburgh, and you know, when you're around something that's so good, it makes you want to do it yourself. Looking at Andy Warhol's prints just makes me want to get out some paint and just get creative in the visual realm. So I grew up listening to music that made me want to make my own music and so that's the goal really, because I don't think we make nearly as much music these days as we could be and, you know the world is not a very peaceful place and it's not a very united place.

I know over here in the States there's a lot of fear and suspicion and it's a very divisive climate, and it's from the top down, really. I think music-making is the antidote to that. Music-making really brings people together. It's very social, it's very enjoyable, anybody can do it. It connects us to our past, it connects us to the stories that we can tell other people. If somebody else is connected to their culture that's different from mine then we've got something we can pass back and forth.

There's just all this insanity now about this whole immigration into the US, particularly from Mexico and the South, and it's just lunacy, you know. It's created this climate of fear and suspicion and I think that, really, people are coming here with so much to share. So much culture, so much music. And I think the more we make music with each other, the more we're reminded of that. And it gives us a sense of what life can be. So people might call it kids music or something, but for me, I call it social music. Because that's the name of the game, really, it's what we do with each other. But we're at that point in America where we're not a particularly musical society anymore. But I really think that could change. You know I'm not a big complainer, I'm just sort of calling it what it is. I really believe that that can change.

The thing that got me especially excited in the beginning was going to the park. A lot of the people here that are babysitters are from the West Indies, so we'd go to the park and hang out with these West Indian women and they would teach me songs. They were pretty cool about it, they were happy that somebody was asking these questions and was interested in their culture, and I was just thrilled that they were so willing to teach them to me, so we spent a lot of time together and a bunch of them ended up forming a group, and that group is on the first record, they're called the Sandy Girls.

That made me realise that a lot of this stuff was just here for the asking, it's a cultural goldmine, and it also made me think about my own heritage. You know, if someone were to ask me about songs that I grew up with, what would I really have to say? So it got me thinking too. Like I said, I don't feel like I do enough. Hopefully the next CD we do will be a lot of songs from Latin America, Mexico on down. That's really exciting me. But every day there's new ideas. Everybody's here. I just love good music. I love great songs, I love stories. It's all around me. It makes me so insane when there's this suspicion and this feeling that we should try and keep people out or make it hard to get here, to America. These people are what's making America great!

And so on. Good dude. Not a bad show, and the kids mostly seemed to be having a swell old time. But who knows, I'm not a two-year old. And this post has gone on way too long.

3 comments:

Waterloo isn't really disco, though - is it?

No, but it's the closest I could get to support my very shonky thesis, which really rested on about two and a half songs anyway. What one could charitably call 'padding', or more cynically term 'hoping the reader will have sort of tuned out by this point, and is just scrolling down to see where this thing ends up'.

IT'S LIKE STEPHEN GLASS ALL OVER AGAIN.

JUKT MICRONICS!

Post a Comment