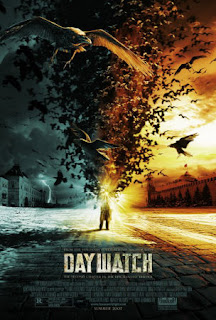

DAYWATCH

As Boney M so astutely put it: “Oh, those Russians!” Since the Cold War ended, pretty much everyone in the West has been carefully watching former Soviet states for the inevitable grudges which will still be lurking around like the smell of the rancid zharkoye your babushka left on the counter yesterday. But while capitalist swine have been suspiciously eyeing the spaces once obscured by an iron curtain, those in Russia have been busy making the kick-assing-est films ever seen!

My last run-in with a Russian mega-movie had kicked my behind so bad I was sleeping on my side for weeks. That was Nightwatch. When I heard that its sequel Daywatch would be screening this year I of course checked the bathroom cabinet for the array of rump-soothing salves and lotions I keep stocked for just such emergencies and hot-footed my way to the cinema. I won’t lie – I was wary, having been burned before by such lacklustre sequels as Porkys II, Dumb and Dumberer and the straight-to-DVD follow-up to The Little Mermaid. I’m still dealing with those.

Nothing doing here, though, since Daywatch took my reservations and cancelled them like an unscrupulous maitre d’! Does that simile make much sense? Of course not! Does Daywatch! Of course not! But it’s still the greatest cinematic event since the last really, really good cinematic event!

The story tracks the conflict between the forces of darkness and light and the factions who police the boundary – the Nightwatch and Daywatch. They’ve all got magical powers that seem to be invented whenever the story requires it or whenever it would just make for a great effect. Which is often. The film is kind of like a mystical version of The Matrix, with so much shape-changing, body-swapping, dimension-jumping and time-warping that you barely get a chance to understand who is who, let alone why they’re doing what they’re up to or why we should really care about any of it. We care because we have to, and we have to because we’re having a fantastic time and are a little bit afraid of these Russians and their superior filmmaking abilities.

If you haven’t seen Nightwatch, this film will make even less sense, but if you have seen it then know that this is an even better movie – tighter, more spectacular and full of moments that take your breath away. It expands upon the universe developed in the first film, and part of the series’ appeal (I think it’s a trilogy) lies in how it effortlessly suggests a complete alternate reality that isn’t simply encompassed within the film itself but seems to stretch outwards to the limits of the imagination. It’s a bit like Harry Potter – the Harry books aren’t particularly great in themselves, but they seem to get people excited by the way they construct an entire world separate from our own, but recognisable in all the important ways.

Here's a trailer for the film which ends with one of my favourite bits - entirely ridiculous and proudly so.

THE SIGNAL

Daywatch is far from the only apocalyptic film in this year’s festival, which is handy. Like most responsible adults, I spend a good portion of my waking life preparing for one of the various doomsday scenarios which seem increasingly inevitable, but I’m not so deluded as to think that the whole otherworldly demon angle Daywatch promotes is anything other than fantasy. No, I’m completely aware that a zombie plague is a much more likely threat, which is why I keep my one-bedroom fortified garret stockpiled with munitions, tinned food, and medical supplies. I also refrain from developing any particular relationships with other humans, since that will only make it harder to put one between the eyes of a loved one when the shit goes down, and when I wake up each afternoon I’m already repeating my self-help mantra: every day, in every way, I am getting better (at headshots).

I’m fully supportive of the new wave of zombie flicks, then (I suppose film theorists would call it nouveau undead or something equally catchy). They just help reaffirm my world view and increase my confidence in the role of paranoid loner which I have attempted to carve for myself. I was a little confused at the end of post-zom film The Signal, then, which posited a situation even I couldn’t quite make sense of. In a minor moment, some characters who’ve survived mankind's degeneration into savage killing machines do a bit of looting, which is one of the perks of any apocalypse. But their wardrobe restock seems to take place in a thrift shop. Does that make any sense? It was then that I realised how far away from my goal I really am, since clearly the only sorts who will survive a zombie outbreak are the kinds whose outfits are entirely made up of second-hand army fatigues purchased for a few bucks a pop.

The Signal is obviously quite effective horror, but it is so in more than a sartorial sense. Like 28 Days Later, its monsters aren’t shambling creeps with a bucket of ugly dumped on their heads, but are fast-moving, cunning monsters. It’s a bit like the Pulp Fiction of zombie films, too, with a fragmented narrative following a handful of characters whose interlocking destinies criss-cross throughout. Some kind of signal is being broadcast through all electronic equipment and anyone who hears it quickly loses all social censures and starts killing people in order to get whatever they want. A few folks still have ambitions beyond adding to the body count and so we watch as they attempt to escape.

Fans of zombie films will enjoy the fresh take it has on the genre, while horror fans in general will get plenty from its overall inventiveness. Those averse to blood and guts should very well avoid this, however. It’s very gory, though the central third of the film (it was directed in three parts by a trio of friends) is almost entirely comedic. The light touch provides some welcome respite from the terror, but soon enough it’s back into to the hedge clippers, power drills and decapitations.

I’m fully supportive of the new wave of zombie flicks, then (I suppose film theorists would call it nouveau undead or something equally catchy). They just help reaffirm my world view and increase my confidence in the role of paranoid loner which I have attempted to carve for myself. I was a little confused at the end of post-zom film The Signal, then, which posited a situation even I couldn’t quite make sense of. In a minor moment, some characters who’ve survived mankind's degeneration into savage killing machines do a bit of looting, which is one of the perks of any apocalypse. But their wardrobe restock seems to take place in a thrift shop. Does that make any sense? It was then that I realised how far away from my goal I really am, since clearly the only sorts who will survive a zombie outbreak are the kinds whose outfits are entirely made up of second-hand army fatigues purchased for a few bucks a pop.

The Signal is obviously quite effective horror, but it is so in more than a sartorial sense. Like 28 Days Later, its monsters aren’t shambling creeps with a bucket of ugly dumped on their heads, but are fast-moving, cunning monsters. It’s a bit like the Pulp Fiction of zombie films, too, with a fragmented narrative following a handful of characters whose interlocking destinies criss-cross throughout. Some kind of signal is being broadcast through all electronic equipment and anyone who hears it quickly loses all social censures and starts killing people in order to get whatever they want. A few folks still have ambitions beyond adding to the body count and so we watch as they attempt to escape.

Fans of zombie films will enjoy the fresh take it has on the genre, while horror fans in general will get plenty from its overall inventiveness. Those averse to blood and guts should very well avoid this, however. It’s very gory, though the central third of the film (it was directed in three parts by a trio of friends) is almost entirely comedic. The light touch provides some welcome respite from the terror, but soon enough it’s back into to the hedge clippers, power drills and decapitations.

FIDO

But zombie comedy, it seems, is all the rage. If rom-com is the accepted shorthand for romantic comedy, it shouldn't knock the yellow off your teeth when you get the pun surrounding the corporation at the centre of Fido, ZomCom. The world on offer here has survived a zombie plague by creating metal collars which subdue a zombie’s appetite for human flesh, effectively turning them into docile servants able to fulfil all of the menial tasks of society. Humans enjoy a picture-perfect life of leisure while the undead collect their garbage, serve their martinis and paint their white picket fences.

This is Pleasantville or The Stepford Wives given a zombie twist, and I really didn’t expect it to be as much fun as it is. I didn’t really grow up with the Leave It To Beaver world the film satirises, but it’s smart enough on several levels to appeal to a wide audience. Beneath the surface veneer of 1950s technicolour sterility, fertile veins of class and race are tapped – subservient zombies occupying the role of the oppressed everywhere – while an equally rich current of familial tension urges the story along. Our hero is a ten year old who finds himself dangerously sympathetic towards his new house attendant Fido (Billy Connolly) while his mother (Carrie Ann Moss) discovers in the undead manservant a caring soul more human than her neurotic and quivering husband. Meanwhile, the retired army hero next door thinks of zombies as nothing but threats waiting to be eliminated, and wants to teach the young lad just how dangerous the undead can be. It's all campy humour with an undercurrent of seriousness that hits just the right balance.

RED ROAD

It seemed odd to cast Connolly as a zombie, since this means that the comedian doesn’t actually get to utter a word of intelligible dialogue. But after watching Red Road, it kind of made sense. Set in Glasgow, its characters’ accents are so thick that at times I felt I was watching zombies groaning for brains in burberry scarves. This is the Chav Apocalypse, and it’s more depressing than any actual undead film could be.

The story follows a woman, Jackie, who works in a Glaswegian police surveillance firm, watching a bank of monitors which track the areas in and around a local high-rise for illegal activity. One day she spots a guy who has featured as some kind of villain in her past, and gradually enters his life for reasons we can’t at first comprehend.

It doesn’t get much bleaker than this. The realm Jackie enters is uniformly depressing as the dregs of society shuffle through an aimless existence amidst grim concrete surrounds. A different soundtrack and you’d have a zombie film right here. Our protagonist’s solution to her woes, along with the tentative redemption that follows, are so painful to watch that they border on walk-out stuff, but at least they’re original enough to make for an unforgettable watch. For better or for worse.

When I compare the film to a zombie flick, I’m not just being facetious. Are there connections between films which cause us to revel in and be repulsed by bodily carnage, and those that give us the same experience rendered on an emotive level? Is watching a character’s psychological disintegration more worthy than watching a character torn apart by bloodthirsty fiends? Answers on a postcard.

No comments:

Post a Comment